How would you define “good” and “bad” art?

Art is an inherently subjective domain, encompassing a vast range of forms, mediums, and intentions. What might be considered “good” art to one person can be viewed as “bad” or unremarkable to another. Despite this subjectivity, discussions about art often revolve around the idea of quality, with people trying to define what makes art “good” or “bad.” But how do we even approach this question? What standards do we use to evaluate art, and how do cultural, historical, and personal factors play a role in this assessment?

The Subjectivity of Art

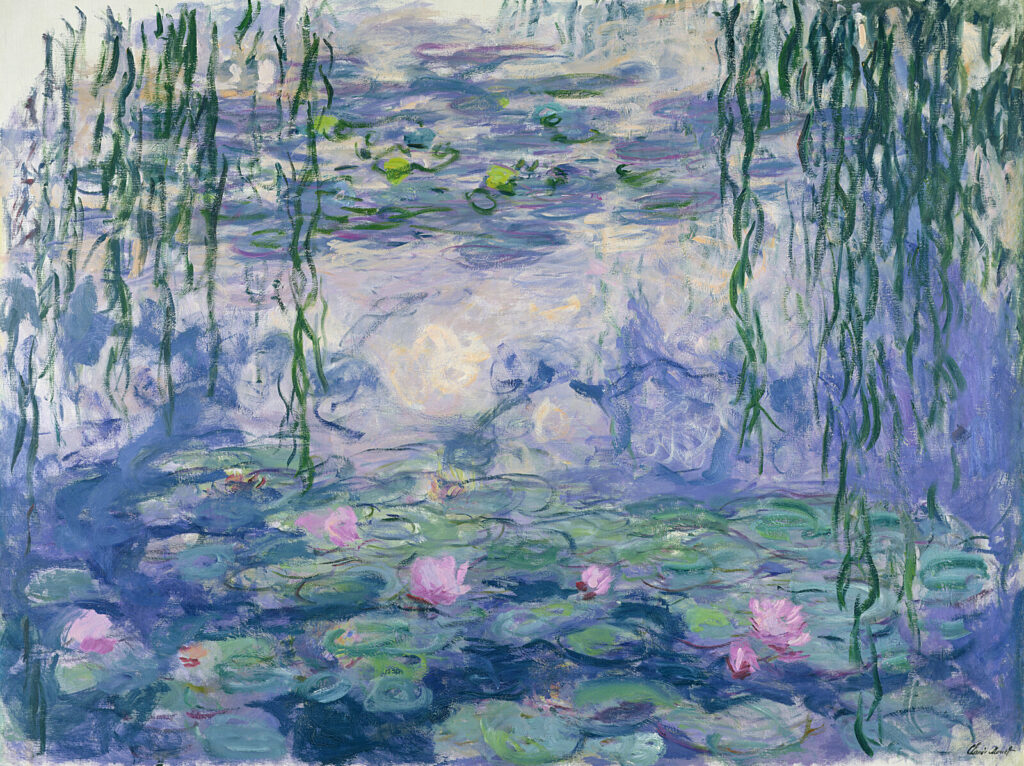

The very nature of art suggests that its evaluation is not a simple, one-size-fits-all process. Whether it is a painting, a piece of music, a sculpture, or a poem, art resonates differently with different audiences. It speaks to people in diverse ways, triggering varying emotional, intellectual, and aesthetic responses. Some people may appreciate the technical skill behind a work of art, while others may prioritize emotional impact or conceptual depth.

The philosopher Leo Tolstoy famously stated that “art is a means of union among men, joining them together in the same feelings.” Art’s effectiveness, according to Tolstoy, could be measured by how well it communicates the artist’s emotions or ideas to the audience. Under this view, good art would be art that conveys something universally recognizable, fostering shared experiences or feelings. However, Tolstoy’s perspective also implies that art that fails to evoke a common understanding or emotional resonance could be deemed “bad.”

But if good art can be defined in terms of its ability to communicate effectively, is there a place for abstract, conceptual, or avant-garde art that might not be immediately accessible? For example, much of modern art, from Jackson Pollock’s splattered paintings to the conceptual works of artists like Marcel Duchamp, challenges traditional notions of representation and beauty. Can these works still be “good” art if they fail to meet conventional expectations?

Criteria for “Good” Art

In the search for an answer, various criteria have been proposed over time to distinguish “good” art from “bad” art. Some of these standards are more universal, while others are highly dependent on personal taste and historical context.

1. Technical Skill and Craftsmanship

One traditional measure of good art has been the artist’s technical skill. For centuries, artists were judged by their ability to master the medium they worked in—whether it was oil painting, sculpture, or classical music composition. For example, the Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo were celebrated not only for their creative ideas but also for their impressive technical execution. Today, this still holds true in certain artistic disciplines, where an artist’s command over their materials and their technique is seen as an important marker of quality.

However, this criterion can be problematic. Many modern and contemporary artists, such as Andy Warhol or Jeff Koons, intentionally subvert technical skill and craftsmanship in favor of conceptual exploration. These artists emphasize the idea behind the work rather than the skill involved in its production. In such cases, the focus shifts from technique to other considerations, such as originality and thought-provoking content.

At Painted Canvas we offer a variety of GOOD art.

2. Emotional Impact and Resonance

Another criterion for evaluating good art is its ability to provoke emotional responses. Art has the power to elicit joy, sorrow, anger, wonder, or even confusion. For many, the emotional impact of a piece is the most important measure of its quality. This idea is particularly prominent in the world of music, literature, and theater, where the emotional experience of the audience is central to the art form.

For instance, a piece of music may be considered “good” if it moves listeners emotionally, whether it is through a heartbreaking melody, an uplifting rhythm, or a powerful lyric. Similarly, a poem or novel that resonates with readers on a deeply emotional level is often considered to have artistic merit. This emotional connection is what makes art feel vital and meaningful. But again, not all art seeks to evoke such a response. Some works may be deliberately cold or cerebral, challenging viewers to think rather than feel.

3. Innovation and Originality

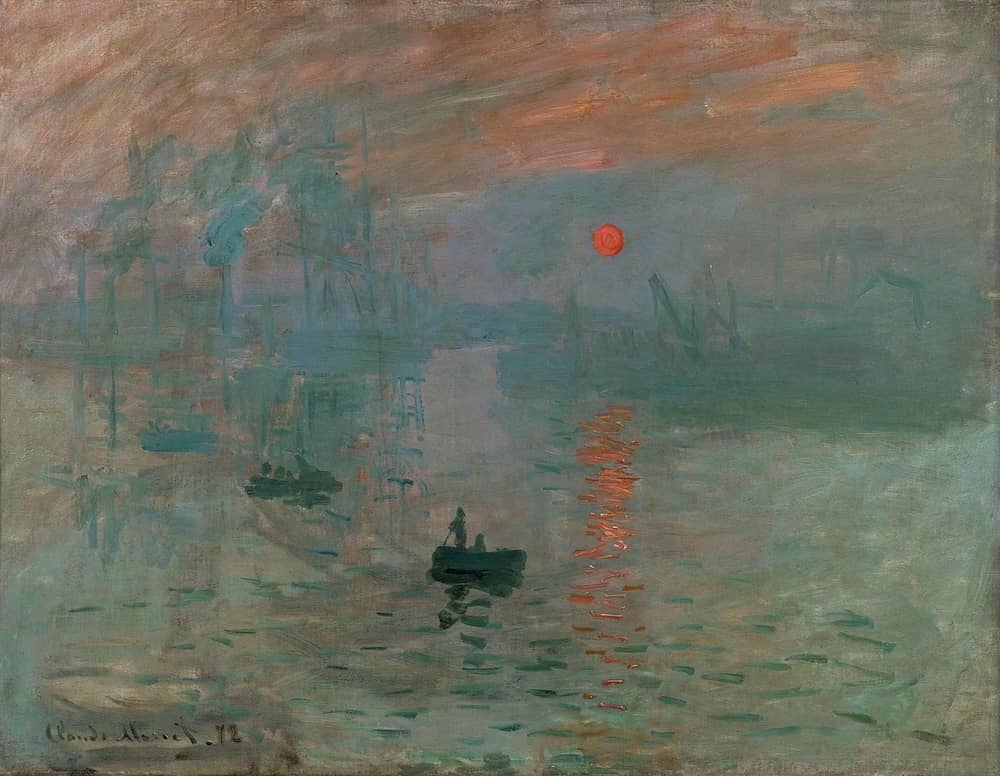

In many cases, “good” art is seen as that which pushes boundaries or introduces new ideas. Innovation has long been a hallmark of artistic value, and art that challenges traditional forms or explores novel ideas is often celebrated for its originality. This is evident in movements like Cubism, Surrealism, and Abstract Expressionism, where artists deliberately broke from established conventions to explore new ways of seeing and experiencing the world.

The flip side of this criterion is the accusation of “bad” art being derivative or unoriginal. Art that simply rehashes old ideas without adding anything new or challenging the status quo may be dismissed as uninteresting or uninspired. However, this too is a contentious point—many artists intentionally draw on past traditions, seeking to reinterpret or respond to previous works, rather than break completely from them.

4. Cultural Relevance and Meaning

Art’s connection to culture and society is another aspect of its evaluation. Good art often speaks to the times in which it is created, offering insight into the cultural, social, or political climate. For example, works of art produced during periods of social upheaval, such as the civil rights movement or post-war Europe, often carry significant weight in both their immediate context and in their lasting impact on future generations. The relevance of a piece to its time, or its ability to address universal themes such as love, injustice, or identity, can elevate its status as “good” art.

On the other hand, art that fails to address relevant social issues, or that seems out of touch with contemporary concerns, may be criticized as lacking meaning or significance. However, the idea of cultural relevance is fluid, changing as societies evolve. What may have seemed irrelevant or “bad” art in one era might be re-evaluated as groundbreaking or important in another.

What Makes “Bad” Art?

The concept of “bad” art is less frequently discussed in a formal sense, but it is often defined in contrast to the criteria we use to assess “good” art. Bad art might be dismissed for being technically incompetent, emotionally hollow, overly derivative, or culturally insignificant. However, as with all forms of evaluation, this is subjective and prone to biases. Art that fails to meet certain standards might still resonate with individuals, particularly when judged through the lens of personal preference.

It’s important to note that “bad” art can sometimes be a matter of context. What might seem trivial or poorly executed in one setting could become highly valued in another. For example, folk art or outsider art—often produced by self-taught artists with little formal training—might be dismissed by traditional critics but hold immense cultural value. This blurring of the lines between “good” and “bad” art challenges us to reconsider our assumptions about value and creativity.

Conclusion: The Fluidity of Art Evaluation

Ultimately, the distinction between “good” and “bad” art is an ever-changing, dynamic conversation. Art’s power lies in its ability to provoke thought, stir emotion, and question assumptions. In evaluating art, we must acknowledge its multifaceted nature and the diverse ways it can resonate with individuals and cultures. What one person sees as a masterpiece, another may view as a failure. This is the beauty of art—it is not bound by rigid definitions but exists as a living, breathing reflection of human experience.

In the end, perhaps the best way to define good art is to embrace its ability to challenge us, surprise us, and make us reflect on the world in new ways—whether through technical brilliance, emotional depth, intellectual provocation, or cultural significance. The line between good and bad art is not fixed; it evolves, shaped by time, culture, and the ongoing dialogue between artists and their audiences.